Using industrial heritage as the design driver for a public park

A former industrial site on the harbour in Sydney’s inner west has been converted into a generous and exciting public park. Far from removing its industrial past, the design of the park celebrates this heritage by playfully reinterpreting and repurposing left-over structures and exposing the site’s multiple layers of history.

The 2.8 ha waterfront site at the eastern end of the Ballast Point peninsula was a Caltex fuel storage and oil distribution point until its closure in 2002. The site is a steeply graded headland with a sharp drop down to the water level – a prominent landmark in this inner western section of Sydney Harbour.

Claiming the site for public land

After Caltex vacated the site, Ballast Point had been destined for medium-density residential development. However, following a strong campaign from local residents and the local council, the site was purchased by the NSW Government in 2002 and set aside for a park.

This was a significant win for public amenity in an area with a high population density, high land values and ever-increasing pressure for further residential development.

The brief for this park was written by the local community in conjunction with the Sydney Harbour Foreshore Authority. It called for a park that responded to the site’s history, that was environmentally responsive and set a benchmark for high-quality parkland on Sydney Harbour.

McGregor Coxall, Landscape architects

Drawing design inspiration from the site’s industrial heritage

The headland’s natural landform had been radically reshaped over the previous decades and had been left honeycombed by industrial uses. Return to a “natural” layer was not an option.

In response, the master plan advocated retaining the site’s industrial character, keeping a substantial amount of the industrial fabric, and giving the site a new robust layer of terracing. This was an important decision that set the direction for subsequent design work.

The site’s industrial past became both an inspiration and a resource for the new park. Existing structures and materials have been kept on site and repurposed. Several large oil storage tanks remain in situ, and the footprint of removed oil tanks has been interpreted in the landscaping.

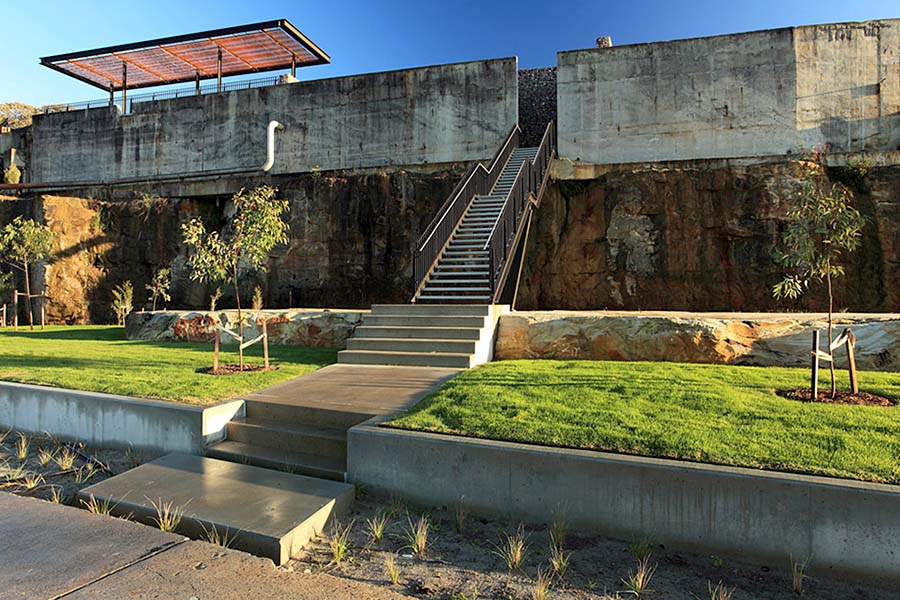

New works were inspired by the paired-back engineering design approach that characterised the site’s industrial structures. Re-using existing materials as much as possible, concrete retaining walls, steel steps, and gabion walls have been constructed to provide a series of fascinating recreation spaces, lookout points, walking paths, and cycle routes that lead down from the headland to the waterfront, and connect into the network of surrounding streets.

A new shade structure and public amenities have been designed to have a similarly robust character, using details and materials inspired by the industrial heritage, and repurposing materials from the site where possible.

The designers decided that “standard” park play equipment would not be appropriate in this context:

The design challenges the concept of children’s play areas in parks of this nature. McGregor Coxall took the position that they did not want to provide off-the-shelf play facilities but rather see the entire park as an opportunity for adventure, exploration and playfulness.

Landscape Australia, March 2017

Revealing the layers of the site’s history

Responding to the history of the site was an important requirement of the design brief. The site’s industrial history is clearly visible, having been woven into the new fabric through a comprehensive program of material re-use. The rubble of the Caltex structures now fills the site’s gabion cages, and retained former oil tanks, or the footprint of removed oil tanks, feature in the park’s main spaces.

In acknowledgment of the site’s long Indigenous connections, the park has been given the Aboriginal name Walama, meaning “to return”.

The park design thoughtfully acknowledges multiple layers of use, including the existence of “Menevia”, an 1860s Victorian villa; its long use as a quarry for ship ballast; as well as the Caltex period, dating from the 1920s until 2002.

The footings of “Menevia” were an unexpected discovery, uncovered during early site work. In response, glass display cases have been installed on site to exhibit the domestic artefacts that were found during archaeological investigations.

This responsive design approach, in consultation with the contractor, was used for much of the new work. The design was adapted as new issues and aspects of the site were unearthed during the construction period.

Interpreting history through contemporary art and design

Layers of history have also been interpreted through new works, including landscape design, the design of built elements, sculptural installations, poetry, and signage.

The former location of the site’s largest fuel tank, Tank 101, is interpreted through a new structure using steel reclaimed during the demolition stage. In a statement referencing the site’s fossil-fuel past, the new Tank 101 is a source of renewable energy with eight vertical wind turbines feeding into the grid and providing power for the park’s lighting.

A poem written by Les Murray titled “The Death of Isaac Nathan” is inscribed across a number of the site’s surfaces. Les Murray lived in the area, and the dingos referred to in the poem are the pair of headlands Ballast Point Head and Balls Head. The words are set into the steel sheets of Tank 101 in a dot typeface representing the many rivets of the site’s steel structures, casting shadows on the surrounding surfaces.

Artist Robyn Backen created a four-metre high concrete cylindrical sculpture, Delicate Balance, inspired by the site’s history as a quarry for ship ballast. The sculpture provides framed views of the harbour and looms over the water’s edge, its metal grate floor open to the sea below.

Leading with sustainable design principles

This project represents a new benchmark in sustainable design; rarely is the issue of sustainability used as the driving force in the design process. This design is premised on using the broken remnants of its previous use as the building blocks for the new.

McGregor Coxall, Landscape Australia, March 2017

Heritage conservation is often an inherently sustainable approach, and in this project these two important goals were successfully aligned in an exceptional way. The site’s history was preserved because very little material left the site.

By adopting a flexible and responsive approach, wherever possible the design was adapted to incorporate existing structures and excavated materials in the landscaping or for new structures. Fill, soil, and mulch were re-used for the landscaping; rubble for the gabion cages; aggregate for drainage and edging; timber for seats, decking, and walls; and concrete for paths and walls.

As an additional sustainability measure, stormwater is captured and used for watering plants, or filtered through on-site wetlands before being discharged clean into the harbour.

Lessons learnt

Heritage projects such as this require a responsive and flexible design approach. With very little geotechnical information or site surveys available at the start, the designers had to make ongoing revisions during construction and work with the contractor to deliver the project.

The demolition and decontamination stages involved a meticulous process of on-site rediscovery, mapping, modelling, and remapping, and the design was modified on an ongoing basis so that no excavated or found material was removed from the site.